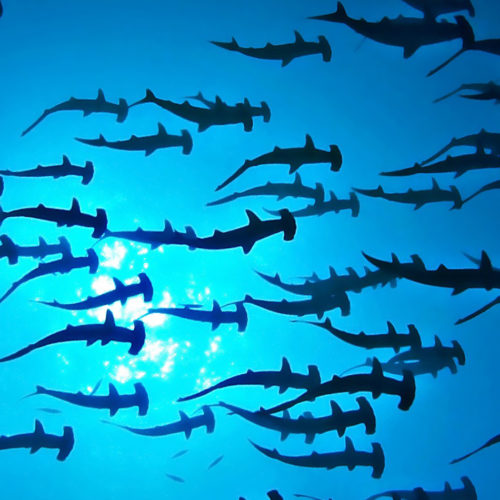

Nestled in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, with the nearest land mass thousands of miles away, French Polynesia is a mosaic of 118 islands and atolls. Picture white sandy beaches, juxtaposed by dark volcanic mountains, and atolls where snorkelling with humpback whales is commonplace. Due to the underwater paradise provided by its deep blue lagoons, French Polynesia is renowned for famous diving spots and being a world-class destination to spot the elusive tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Every year, countless shark fanatics congregate in Fakarava to swim amongst schools of nurse, hammerhead and tiger sharks.

close

What is Pelorus Foundation?

Our mission is to champion innovation and act as a catalyst, empowering individuals and local communities to preserve and protect the world’s wildlife and wild places for future generations.