close

What is Pelorus Foundation?

Our mission is to champion innovation and act as a catalyst, empowering individuals and local communities to preserve and protect the world’s wildlife and wild places for future generations.

Corals are a crucial element of the ocean’s ecosystem with one quarter of marine life calling coral reefs their home, while covering less than one percent of the ocean floor. But with water temperatures rising, and ocean acidification increasing – corals are in danger. By identifying and collecting fragments of super corals in wild, growing and monitoring these in coral nurseries, then planting the corals in degraded reefs – the Coral Gardeners are restoring the extensive coral reefs around the island of Mo’orea, French Polynesia.

Established in 2017 in Mo’orea, the sister island of Tahiti, French Polynesia, the Coral Gardeners are on a mission to plant one million baby corals before 2025. What began as a small group of island children who witnessed the rapid degradation of their local reef and decided to act, has grown today into an international collective of advocates, scientists, engineers, and creators determined to revolutionise ocean conservation. Coral Gardeners have created a global movement to save reefs around the world. Using careful monitoring systems, innovative tech and specialist nurseries, the team has identified the hardiest coral species to transform our fading reefs – and the vitality of our marine biosphere.

One of our contributing writers, Lana Jevremovic, sat down with Evenlyne Chavent, Head of Reef Restoration and Science, to discuss what life as a Coral Gardener looks like – from sourcing super corals, workdays spent in the ocean and the big picture.

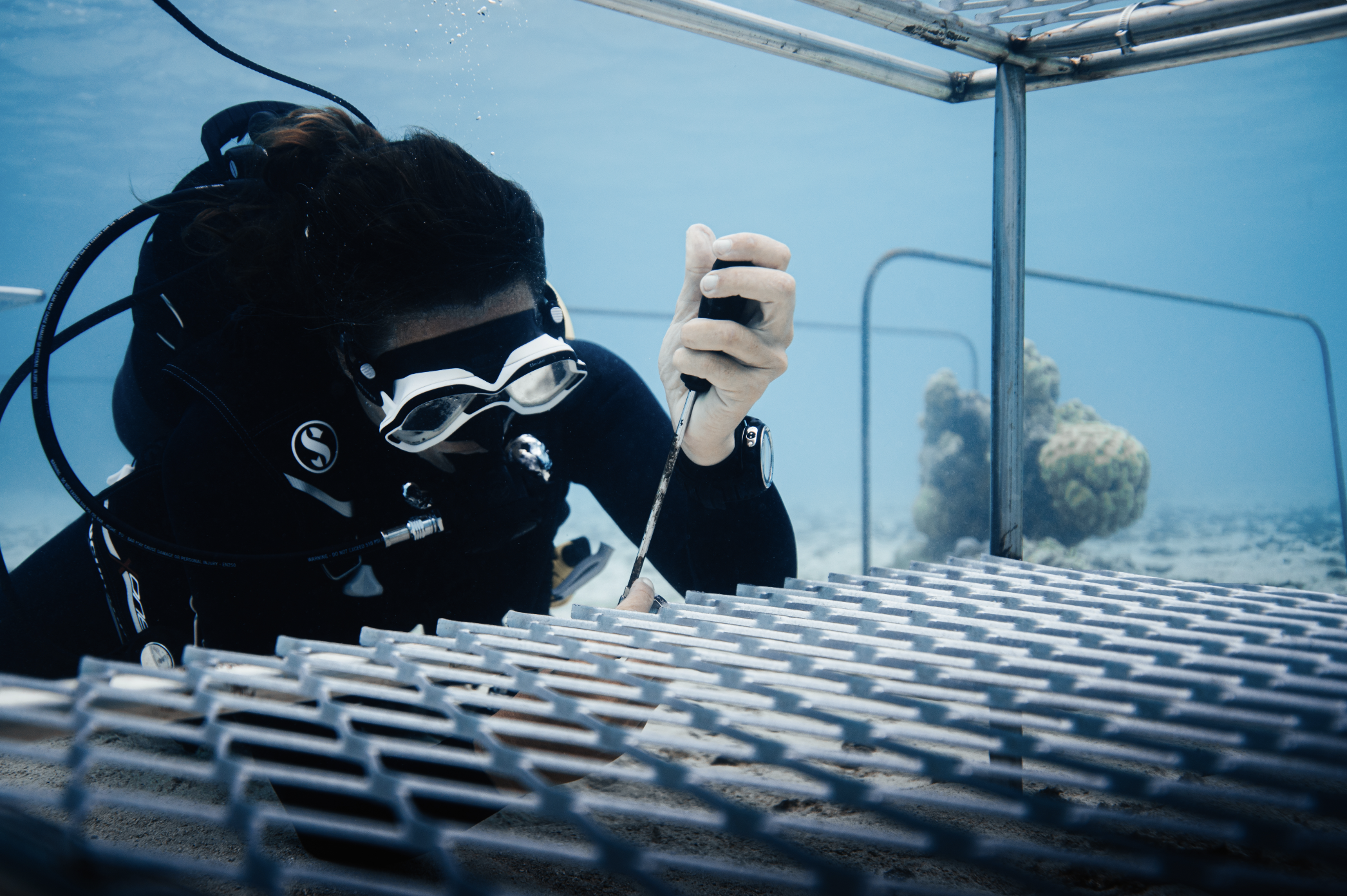

We’re in the water almost every day, if not every day, to maintain the nursery. My job is to set up the so-called gardening method in the nursery – where to establish it, which coral to take, and then where to plant the coral.

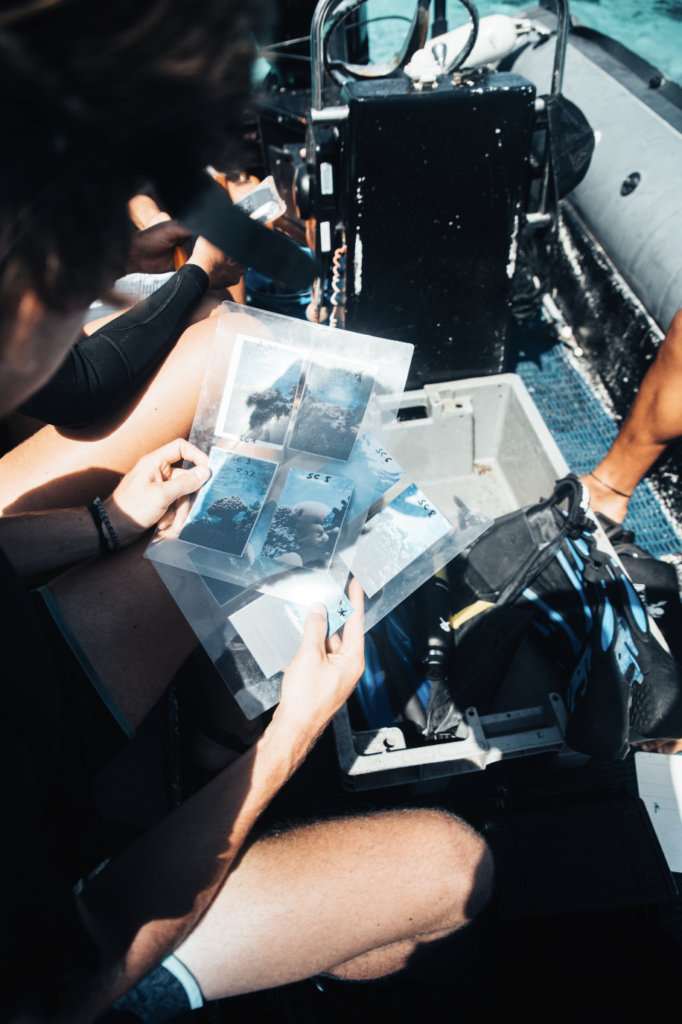

We monitor the corals to keep track of the survival rates – and also the undergrowth of coral so we know how big they are, how much they’ve grown, and how fast. When corals are big enough, we transplant them from the nurseries. Right now, we are about to transplant 5000 or so coral. The monitoring stage takes around a week, so it’s about a week per month.

We know the site we want to raise the corals on so we put the nursery close by this site meaning the corals get used to the depth and the water they will be growing in. We collect corals from a pristine reef at the same depth. We take older corals because we think they can survive more stress and should therefore be better at resisting stress in the future. We call them super coral residents because they are older and have grown very slowly. We take a maximum of 10% of the coral in a fragment, approximately the same damage that a trigger fish could do to a coral. This ensures we don’t impact on the coral colony at all.

It’s usually visible to see the growth in the nursery within three to four months. The latest nursery was put in last September and they have already grown back to three times the size that we put in. And the nursery that we’re going to transplant next week has been in the water for one year and a half. They’ve grown almost seven times the size that they were. This is super-fast, much faster than you would expect naturally.

Well we’re going to keep the coral in the nursery because we don’t want to keep taking coral from the natural reefs. So, in five or so years’ time we can use the nursery as the source for new trimmings. Like giving the old nursery a haircut. We take these fragments and cement them using marine cement into small holes in dead coral. We cement them so they can’t move, and they take a hold and start to grow back. They usually attach themselves onto the rock in about a month so we just need something that will stop the fish dislodging them in that time.

Once we’ve finished the transplant, we look at them from time to time – at the very least, every three months. If the coral is not thriving, we need to find out why. If it’s because there is a predator close by, we can move and place the predator somewhere else. But if they catch a disease, it’s almost impossible. Once they are on the reef, sadly, if they die, we can’t do anything. We just learn from it and say, ‘OK this area is not good’.

Usually, in the first year the average is around 80%. It’s very interesting that even after five years, if the survival rate is 60%, some scientists call it a success which I find quite low. For me 80% after five years would be awesome.

There’s more fish coming back in the area where we transplant compared to areas where we don’t transplant, and there is less disease. Also, they are more corals and a more diverse ecosystem in general. We see more coral recruits because they are attracted by live coral reefs. Coral restoration won’t really impact the water quality as the water quality is impacted by whatever is happening on land. But the journey is parallel – coral restoration and, at the same time, stopping the source of pollution from land runoff.

The long-term goal is by 2025 we’re going to plant one million corals, and to do that we are going to open branches all over the world, between 20 and 30.

The main stressor is global climate change. Water temperature is rising. The level of water is rising and there is more acidification in the ocean, so that’s a massive problem also for corals. That’s everywhere, and then in some places there are human stressors like overfishing, no proper sewage treatment, or any land treatment runoff. So, we try to grow the corals under stress conditions so they can cope with such stresses when they are out in the wild.

At Pelorus Foundation, we too are on a mission to support the growth and protection of coral reefs by supporting grassroots projects working to mitigate the continuous threats from climate change, pollution and overfishing.

Please help support conservation projects in action and make a donation today.